KEES DEKKER SIPPED a glass of Sassi Neri, a Rosso Conero wine, in the cantina of the La Terrazza vineyard and pronounced, “You don’t drink this wine because it’s just wine.”

I nodded, not really knowing if I could fully appreciate the subtle differences in flavor. Visiting this famed vineyard that claimed connections to Bob Dylan, for me, meant drinking free wine in a chilled environment on a blazing summer day, plus the opportunity to learn a little about life in Italy.

Dekker, a Dutchman, savored the dry, fruity taste, paused and then declared, “This is a serious wine; it has complexity.”

He and his wife had been vacationing in Le Marche every summer for the past four years and they were in the process of buying a second home here. They had initially looked in Tuscany and Umbria but they found that Le Marche was cheaper, less crowded with foreigners and far more diverse than anywhere else they had been.

“Italians say that Le Marche is Italy in one region,” Dekker noted. “You have the sea, the mountains, all four seasons.”

Like the wine, there is complexity in the region.

•

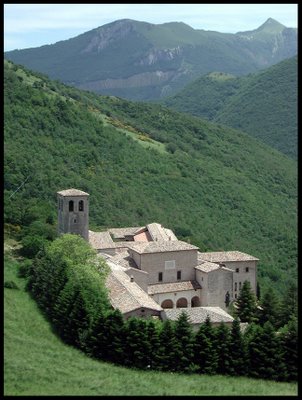

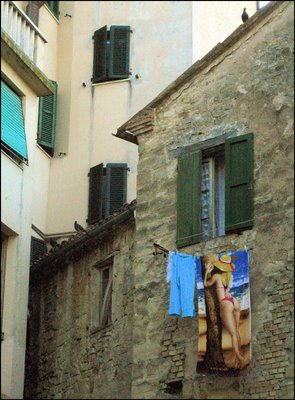

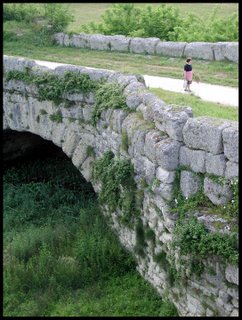

Le Marche begins at the Adriatic Sea, develops into gentle, rolling hills and ends in the massive, mile high Apennine Mountains.

As the terrain subtly evolves from sea level to foothills to high ground, there are minor disparities in people’s attitudes and slight differences in cultures.

Residents of hilltop towns separated by only a few miles have different dialects and opposing outlooks on life. The special delicacy of one town may be unavailable in the next town down the road. The modest style of one city, while not necessarily noticeable to outsiders, may be different from the slightly less modest style of the next.

And that’s the way they like things there.

“In America, things are black or white – things are good or bad,” said Carlo Cleri, a representative of the Slow Foods movement branch in the medieval city of Cagli. “We like variety, difference. There is a lot of range between white and black.”

Wine is a prime example: there are more than 250 government sanctioned varieties of wine produced in Italy, a country smaller than California where there are fewer than 30 varieties.

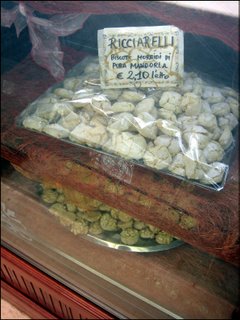

In Le Marche alone, there are 12 types of wine that are created here and nowhere else in the world. Each wine, labeled “D.O.C.” (denominazione d'origine controllata, meaning wine of controlled origin), has its own characteristics that vary, if only slightly, from other wines produced in the region.

You could spend years exploring the hundreds of vineyards that exist in Le Marche, from worldwide production facilities to mom and pop farms. And whether or not you can savor the difference between a full-bodied Rosso Conero and an ethereal Rosso Piceno, touring wineries is a great way to experience the differences in our cultures, as well as the differences in theirs.

•

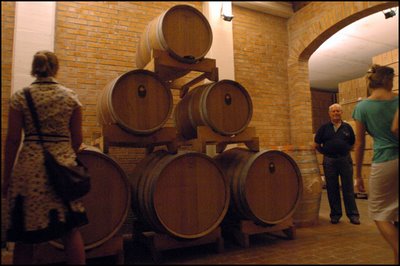

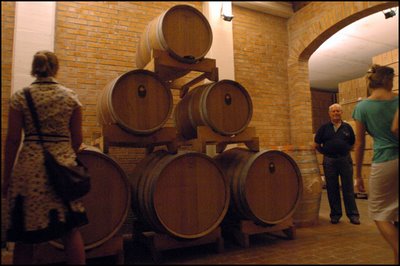

“You’re walking on wine,” Gianluca Garofoli said with a laugh as we entered the original fermentation room of his family’s vineyard near the holy city of Loreto.

The English-speaking, 25-year old Gianluca explained that below the concrete floor at our feet, in two giant concrete tanks, were thousands of liters of Rosso Conero, the cherry-smelling red wine that is only produced in the area surrounding Monte Conero.

The old cellar - ripe with the aroma of sweet wine - was built in 1901 and is still used today even though the Garofoli family has completely modernized their facilities. Wine is also aged in huge, 900 liter wooden barrels as well as in steel tanks. In the basement of the adjacent building are 700 French barrels used to mature wine at 225 liters per barrel.

“Each generation has built this business, step by step,” said Gianluca, whose grandfather’s grandfather started the vineyard in 1871 along the pilgrimage path to Loreto, where the original home of the Virgin Mary has been for around 800 years.

Garofoli, a mid-sized winery with 1,400 acres of grape fields, now distributes 2.2 million bottles around the world annually.

The affable Gianluca, a Red Sox-loving baseball fanatic and heir to the family business, explained that the Garofoli family was among the first vintners to put wine in bottles - rather than jugs - in the latter half of the 19th century. In the 1950’s, they were among the first in Italy to have a fully automated bottling plant.

“We totally changed the distribution of wine in Italy,” he said.

Gianluca eagerly walked us around the state-of-the-art bottling plant where 5 workers watched machines package wine at 5,000 bottles per hour.

Then he offered us wine.

“And now we drink?” he asked.

So we sat down for a few hours, sampled several bottles of Garofoli reds and whites and we talked to Gianluca, the left fielder for the local squad, about life in Le Marche.

“I don’t know if I love the Marche region but Monte Conero is beautiful,” he said as he continued filling our glasses. “Everyone knows it around the world. This is a very good region to live.”

•

Actually, Monte Conero and the Le Marche region remain rather unknown, especially in comparison to great Italian destinations like Rome, Venice and the heavily trafficked Tuscan region.

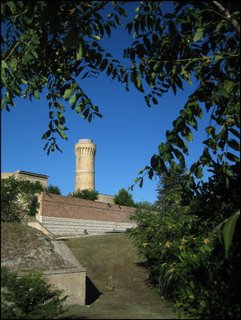

But Le Marche, due east of Tuscany, is a veritable treasure trove of charming medieval hill towns, pristine beaches and stunning vistas.

On a random drive, you can find vast fields of radiant, yellow sunflowers, ancient castles perched high upon mountaintops and charming little villages full of cafes and friendly people who don’t speak a lick of English.

•

When we arrived unannounced on a scorching summer Sunday afternoon, Sandro Finocchi’s 86-year old father was sitting in the shade on the porch of the modest family home, a handful of tiny, lazy kittens sprawled at his feet.

He immediately began talking to us in Italian as though we were old friends.

I had been in Italy for more than a month at that point, teaching in a journalism program for American college students, so my language skills were almost acceptable.

Still, I could barely understand the lively old man. He seemed to be rambling on and on in a local dialect about being a prisoner of war in a Turkish camp during World War II.

Finally, he called for his son, the operator of the Azienda Agricola Finocchi vineyard.

Sandro Finocchi, clad in brown sandals, a black tank top and shorts, approached us with a smile and offered to give us a tour of his 20-acre property even though he was in the middle of eating lunch. His 16-year old daughter Elena acted as our translator.

“I live upstairs and I work here,” Finocchi said. “I don’t leave too much!”

We walked down a gentle sloping hill that was thick with grape vines and olive trees. Finocchi explained that the land had been in his family for generations but he began producing and selling wine in the mid 1980’s. He pulled a small, rubbery branch off of a tree and showed us how he uses the twigs to bind vines to fencing.

“Everything is organic,” he said. “We only use a minimal amount of chemicals to keep away parasites.”

He produces about 40,000 bottles per year, mostly the crisp, white Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi, with much of the wine going to restaurants in Rome. And it is completely a family operation – Finocchi and his two daughters gather the grapes, bottle the wine, place labels on them and then box the final products.

Back at his home/ factory, Finocchi cleaned a few glasses and poured us white wine straight from a stainless steel tank.

“It’s too cold,” he said. “But that’s good for a hot day like today.”

•

Le Marche’s verdicchio wines were popular in the years following World War II and their distinctive hourglass-shaped bottles became symbols of Italian restaurants around the world. As competition for sales increased, wine makers began lowering the quality of the product in order to lower the price.

That caused a backlash and the virtual end of verdicchio sales.

Over the past 20 years or so, Italian verdicchios have made a strong comeback. Some of the whites can now be aged for up to ten years, similar to high quality reds.

•

The fresh, white Bianchello del Metauro wine from the Guerrieri vineyard tastes like Le Marche. You can smell the dry farmland in the glass and you can almost taste the sea air that wafts over the fields.

The grapes are grown in the Metauro River valley, a few kilometers inland from the Adriatic Sea, on 500 acres of land that has been cultivated by the Guerrieri family for more than 200 years.

The grape variety, however, is much older and carries a sense of pride for the locals: legend has it, Luca Guerrieri told us, that the Bianchello del Metauro saved the Roman Empire.

The great Carthaginian general Hannibal had already taken much of Southern Italy when his brother, the commander Hasdrubal, began advancing upon Rome from the north.

On a hot summer night in 207 BC, Hasdrubal’s troops made camp along the Metauro River and found a farmer with vast reserves of Bianchello del Metauro wine. The Carthaginian army reportedly drank gallons upon gallons of the refreshing drink and when the Roman legions attacked in the morning, the Carthaginians were either too drunk or hung over to survive.

Or so the story goes.

•

Of course, nearly all Italian wines are created with American roots grafted onto their vines.

A parasite, phylloxera, caught a ride to France from the U.S. in the 1860’s and, within 25 years, wiped out most of the European vineyards. The solution to the almost-catastrophic event was to create hybrid plants which are still used today.

Some of the grapes produced in the region, like the LaCrima di Morro D’Alba, have retained their ancient flavors.

“LaCrima grapes are a special type of grape,” said Carlo Cleri, 35, the Slow Foods proponent. “It’s traditional, it has the flavor of old wines.”

We had spent the afternoon touring the factory of the Stefano Mancinelli winery, with Stefano’s parents, Fabio and Luisa, as our tour guides. The factory, which specializes in the LaCrima, wasn’t much to look at but the family couldn’t have been nicer to us. They sliced a blackberry pie and invited us to sit and taste their wines. The more questions we asked about them and their rose and violet-scented wine, the more they kept giving us stuff – books, pictures, wine labels.

Fabio Mancinelli began making wine about 50 years ago just for the love of doing so. He grew his own grapes on the hills near the castle-like city of Morro D’Alba. His passion became his son’s business and now they are among the few farms that are allowed to grow the rustic-flavored grapes that can be given the name of LaCrima di Morro D’Alba.

“To me, this is the best wine,” Cleri said. “It is a wine I usually open with a girl.”

•

We visited the Capinera Winery, owned by a pair of BMW-driving brothers who are both architectural engineers in Rome. Paolo Capinera speaks a little English. Fabrizio is a sommelier. They started making wine on 18 acres of old family land near Morrovalle about ten years ago.

The brothers were excited to entertain us but they were also in a rush to go home to Rome, a three-hour drive away. They poured copious amounts of wine for us but rushed our tasting. It made our drive home pretty exciting.

Another day we visited the tourist friendly Conte Leopardi winery in Numana where the owner handed visitors glasses of wine as soon as they entered the shop.

An employee at the Moroder vineyard in Ancona escorted us through the cellar but never offered us wine. So we left.

At the Vicari vineyard in Morro D’Alba, locals were filling up large, 5-gallon jugs with LaCrima.

Silvano Strologo showed us huge, 27-liter bottles of his Rosso Conero at the Strologo vineyard in Camerano.

“I recently sold 3 bottles to someone in Germany,” he laughed.

•

“Of course, Tuscany is always first,” said Laura Baldinelli, an English-speaking export assistant at the Umani Ronchi winery in Osimo. “But Le Marche is very popular now as well.”

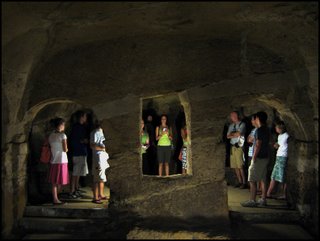

Baldinelli spoke to us inside the 58 degree cellar that is designed to look like the inside a mine.

“Here, there are not diamonds but our top wines,” she said.

The moist, dim room that was as stylish as a nightclub contained 500 French barrels containing roughly 300 bottles of Italian wine per barrel. And that was less than half of the vineyards production. Another 500 barrels were kept at another location and the winery employs dozens of huge, steel tanks.

“We produce 4.5 million bottles every year,” Baldinelli said. “It’s a very huge quantity.”

In the slick, glass showroom afterwards, we sampled six of the vineyards finest wines. And we all walked away carrying bottles to take back to America.

•

Dekker, the Dutchman, purchased 12 bottles of the Sassi Neri wine from La Terrazza.

“We’ll drink two or three every few months and then come back next year!” he said.

It was an admirable plan.

“Le Marche is a wonderful place,” he continued. “But I think if you return in 10 years it will be a very different place, for better or worse.”

- G. Miller

LE MARCHE IS A fascinating place - with vast fields of farmland and huge, sprawling cities.

LE MARCHE IS A fascinating place - with vast fields of farmland and huge, sprawling cities.